Power, yes, but not at any price! Louis Renault already believed that engines should be light in weight. It was with this in mind that he invented a system known as supercharging that made engines more powerful without the need to enlarge them. The system was registered as patent number 327,452 on 17 December 1902. This is how it worked: by increasing the amount of gases allowed into the cylinder on each stroke, greater compression occurred and therefore a more forceful explosion, generating more power. A ventilator or a small compressor controlled by the engine itself was what took the combustible gases to the engine.

The foundations of turbocharging had been laid, although the patent did not yet mention the term. At Renault, the turbocharger was tried out in aeroplanes, where its function was to “supply more air” to the engines at high altitude when oxygen became scarcer. In 1918 the Rateau turbocompressor (from the name of the engineer who developed it) was adapted to work with the 320hp V12 Fe engine in Breguet XIV A2 reconnaissance aircraft.

The Bréguet XIV A2 was fitted with a V12 Fe turbocharged engine in 1918

It was not until the 1970s that turbochargers were used in cars again. And what a comeback that was! After the 1960s when Alpines ruled the rally circuits, Renault decided to put more resources into motor sport. Engine developers at the brand-new Renault-Gordini plant in Viry-Châtillon launched the 2-litre V6, a compact, normally aspirated engine designed to equip an Alpine. When it was fitted to the A441, sparks began to fly in the 2-litre Prototype and Formula 2 categories, and in rallying, but the new engine did not yet have enough horsepower to tackle the toughest event, the Le Mans 24-hour race.

It was Jean Terramorsi, the new head of Viry-Châtillon, who came up with the solution: what if we revived the turbocharger? Thanks to the expertise of engineer Bernard Dudot, a turbocharger was tested in an A110 1600S Berlinette at the Criterium des Cévennes rally in 1972. With an accelerator response time of about three seconds, the turbocharger made the car practically impossible to drive! Even so, Jean-Luc Thérier’s exceptional acrobatic talents brought him an unexpected victory, which also gave the turbocharger a passport for more in-depth research.

The turbocharged A 110 Berlinette made Jean-Luc Thérier the suprise winner of the 1972 Criterium des Cévennes rally

The Viry-Chatillon plant where Renault's turbocharged engines were developed, shown here in 1975

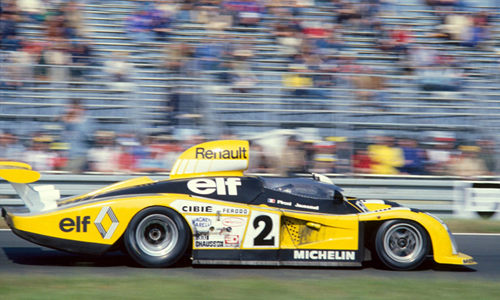

So in 1974 the 2-litre V6 was equipped with a turbocharger. The next year the engine was used to equip the Alpine A441 driven by Jean-Pierre Jabouille, who won several Formula 2 races with it. The A442 with a turbocharged engine took on the Le Mans 24-hour race for the first time in 1976, by way of an experiment, then again in 1977 – but without great success. It was only in 1978, after three years of trials on test benches, engine tuning and broken pistons, that the A442 driven by Jaussaud and Pironi snatched the Le Mans title from Porsche, with an average speed of 201kph and top speeds of 370kph!

The Alpine A442 that Jean-Pierre Jaussaud and Didier Pironi drove to victory in the 1978 Le Mans 24-hour race.

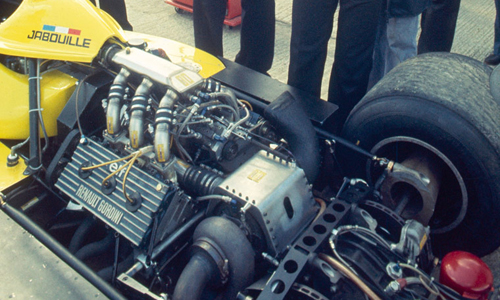

“Well done, and now let’s move on to Formula 1!”, said Bernard Hanon, who was Chairman and Managing Director of Renault at the time. Turbocharging was ripe for the ultimate motor sport. While its rivals lined up 3-litre V8 and V12 engines on the starting grids, Renault entered a relatively small 1.5-litre turbocharged V6. Outside the company, everyone thought Renault was taking a crazy gamble. The first tests were difficult. “I had time to read the newspaper between the moment I pressed the accelerator pedal and the moment the car responded”, Jabouille recalls. What’s more, the car was not as reliable as had been hoped. The first Renault Formula 1 car, the RS01, made its debut at the Silverstone Grand Prix in 1977. It did no more than 12 laps, and earned the nickname “Yellow Teapot” in the UK because of the cloud of smoke it emitted when it came to a halt with a wrecked turbocharger.

But Renault kept the faith. In 1978, after more relentless research to improve reliability – especially materials – Jabouille’s RS01 finished fourth in the United States Grand Prix, then scored the car’s first win at the French Grand Prix on the Dijon circuit in 1979. René Arnoux drove the other RS01 to third place. It was a historic date: for Renault, which won 19 other Grands Prix and narrowly missed the 1983 world title with Alain Prost before withdrawing from the circuits in 1986, but also for the whole of Formula 1 because the use of turbocharging – which so many people had been making fun of a few years earlier – became the norm during the 1980s. The race for power got quite out of hand, with some engines delivering about 1,500hp[1]. The debate became so controversial that turbocharged engines were banned from Formula 1 in 1989 because they were considered too dangerous.

The RS01 at the Silverstone Grand Prix in 1977 : Renault's first F1 victory

The RS01 engine : a turbocharged Renault-Gordini 1492cc V6

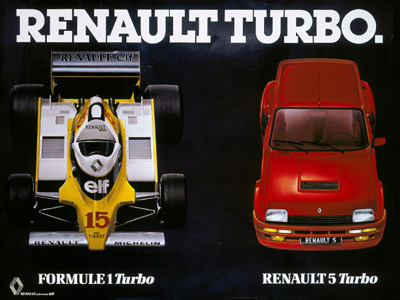

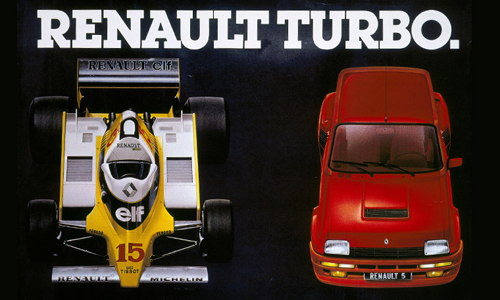

From F1 to production models… As a pioneer of turbocharging in motor sport, Renault decided to make this leading-edge technology accessible to all. In particular, it meant current production engines could be made to perform better for a lower investment. In 1980 the Renault 5 Turbo was launched with a turbocharged Renault 5 Alpine engine (Cléon, cast iron, 160hp, 1.4l turbo). The racing version began its career in 1981 by winning the Monte Carlo Rally, with Jean Ragnotti at the wheel, and the French rally championship, with Bruno Saby – the start of a long series of victories. In 1981 the R18 Turbo went on sale equipped with a 1.6-litre aluminium engine produced at Cléon and delivering only 110hp, but with torque capacity that was extraordinary for that time. Next came turbocharged versions of the Fuego, Renault 11, Renault 25, Renault 9… The Renault 21 Turbo, which in 1987 was given a Douvrin 2-litre engine, could reach a top speed of 227kph on the racetrack! That was the culmination of turbocharging devoted to power, and the famous “kick up the backside” for acceleration.

Renault used its successes in F1 to launch the Renault 5 Turbo (1980)

The Renault 5 Turbo on the road (1980)

Turbocharging to boost energy efficiency and downsizing. In the 1990s, cars grew more “responsible”. As laws to improve road safety were tightened and motorists started looking for environment-friendly cars that cost less to run, making vehicles more powerful was no longer the main issue. The dilemma now facing carmakers was: how could they make their engines more efficient – using less fuel and causing less pollution – while retaining their power? Once again, the answer was… turbocharging!

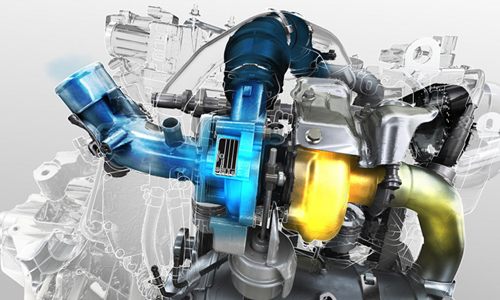

The technology first made a comeback with diesel engines, helping them to use less fuel and respect increasingly strict emissions norms. This was the DT (Diesel turbo) range, crowned by the dTi (direct-injection Diesel turbo): in 1997 the 1.9 dTi was the first French direct-injection turbocharged engine. In 2000 all Renault’s diesel engines were equipped with turbocharging (the dCi range). The system was further enhanced by common rail technology, then by variable-geometry turbochargers, which made the engines more efficient by boosting torque at low revs, thereby saving energy. By way of example and at comparable power, the Laguna launched in 1994 with an 85hp 2.2-litre diesel engine was later equipped with a 100hp 1.9 dTi unit, then a 110hp 1.9 dCi unit, then a 110hp 1.5 dCi version.

The 1.9 dTi (F9QT) : direct-injection turbocharging.

The Energy 1.5 dCi (K9 Gen6 turbocharger.

Turbocharging was used again with petrol engines from the year 2000, with a downsizing strategy following the same trend started with diesel engines ten years earlier: a 165hp 2-litre turbocharged engine for Vel Satis, and above all the TCe 100 (only 1.2 litres for 100hp) that in 2007 equipped Twingo GT, Clio III and Modus. Since 2011 the Energy range of engines has acquired even more power per litre: TCe 90 (0.9 litres) and TCe 130 (1.2 litres).

Energy TCe 90 (H4BT)

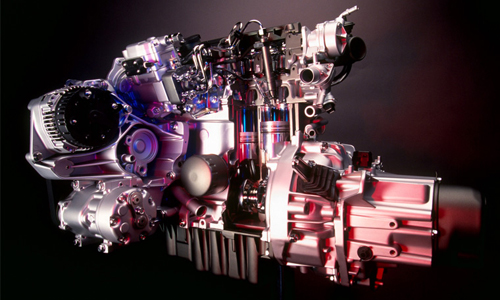

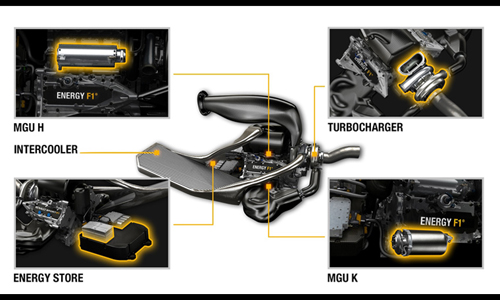

In 2014 turbocharging will be returning to Formula 1 – used in the new Renault Energy F1 engine. Here too downsizing is the watchword: the former RS27 developed 750hp for 2.4 litres, whereas the Energy F1, a 1.6-litre turbocharged unit, will deliver 600hp plus an extra 150hp from brake energy recovery. Combined with electric technology for dual energy recovery, its fuel consumption has been cut by 40% – a key concern for production models.

The Renault Energy F1 engine, for the 2014 season

Turbocharging is still answering a demand that has remained constant throughout Renault’s history: the need for efficient, economical engines…

[1] By way of comparison, the Renault RS27 (2013 season) developed 750hp.

View more

SAFETY: 5 EURO NCAP STARS AND BEST RATING IN ITS CATEGORY FOR THE ALL-NEW CLIO

The All-new Renault CLIO: the most comprehensive driving assistance on the market